In August 2022, I presented a talk “Going Atomic: The Strengths and Weaknesses of a Technique-centric Purple Teaming Approach” at Blue Team Con. As the talk wasn’t recorded, and my slides were relatively sparse, I thought some might find it useful to have a write-up of it to digest alongside the slides (which are available here).

Introduction

Purple team exercises are an ever more popular offensive testing activity for vendors and internal teams to perform. Done well, they bring together the knowledge of threat actor tradecraft from the ‘red’ side of the house, with the defensive focus of the ‘blue’ side, to assess, develop and maintain defensive capability.

Offensive Informs Defense

It’s a well-worn cliche to say ‘offense informs defense’, but in the unique context of adversarial emulation there’s nuance to it that’s worth considering.

Different forms of offensive testing inform different areas of our defense.

If we take a red team, for example - think a ‘full-chain’, covert, objective-based exercise - we’re testing all manner of defensive aspects, from our detection capability, to our response playbooks and processes, to the success of our user awareness training.

While not an activity many would consider classically ‘offensive’, a table top exercise does well to inform aspects of defense too. It allows us to test our response to a fictitious incident, and better understand how prepared… or unprepared… we are for a fully-fledged crisis. It gets our senior leaders in a room, alongside representatives from legal, technology, and more, and asks tough questions as to whether a ransom should be paid, when production systems should be brought down to protect the business, and what message should go out to the press.

So what part does atomic purple teaming play in informing defense?

Atomic vs. Scenario-based Purple Teaming

I would hazard a guess that for many, ‘purple teaming’ is most commonly considered to be a scenario-based exercise. An exercise not necessarily too far removed from a red team in terms of its technical delivery, but where defenders have some point-in-time understanding of what is taking place.

I’ve seen collaboration between red and blue in such purple teams to vary wildly, and can range from red and blue being co-located, so blue can get a feel for the attack process and what commands are being executed, etc. Through to details of domains and IPs, as well as potentially internal hosts used for assumed breach, being shared in advance to let the blue team know not to kick off an incident if/when alerts start bubbling up in the SIEM.

Let’s take an example of a scenario-based exercise. We’re emulating a ransomware group, based on the TTPs disclosed in everyone’s favourite emulation reference material, the Conti playbook. Considering an exercise that moves through an attack chain, achieving initial access, execution, persistence, and so on. There are several significant benefits of such an exercise, namely:

- We’re achieving emulation potentially down to a procedural level.

- We have an evidence-based appraisal of our defenses against a given threat.

- We have the potential to exercise response playbooks and processes.

Where high-quality threat intelligence is available, which the Conti playbook undoubtedly is, we can run the commands as close as reasonably possible to how a legitimate actor would. Therefore, understanding exactly how our security tools, use cases, network design, etc. would fare in the event the actor performed their previously observed methodology against us.

Such information is great ammunition to fend off senior leadership when they get wind of something like the Conti playbook. We can confidently tell them, with data to back up the statement, ‘we’d probably be ok’.

We also have the opportunity to use such an exercise to test our response playbooks and processes. While we could do the same with something like a red team exercise, by comparison, a collaborative purple team is a far safer space for trying new things, seeing what works and what doesn’t, without the pressure of knowing we’re being assessed, and need to contain this threat as quickly and effectively as possible.

We considered how red teams and table top exercises informed our defense, and now we’ve thrown scenario-based purple teams into the mix to fill in some of the gaps too. But what doesn’t scenario-based purple teaming do for us?

Dechaining execution and maximising coverage

For a scenario-based purple team exercise, we likely have a handful of techniques we’ll aim to execute at each stage of the kill chain. Considering our Conti playbook again, this could be things like net and nltest commands for Discovery, ZeroLogon for some privilege escalation and maybe a sprinkling of avquery on the command line before we realise that should’ve been run in Cobalt Strike not Command Prompt.

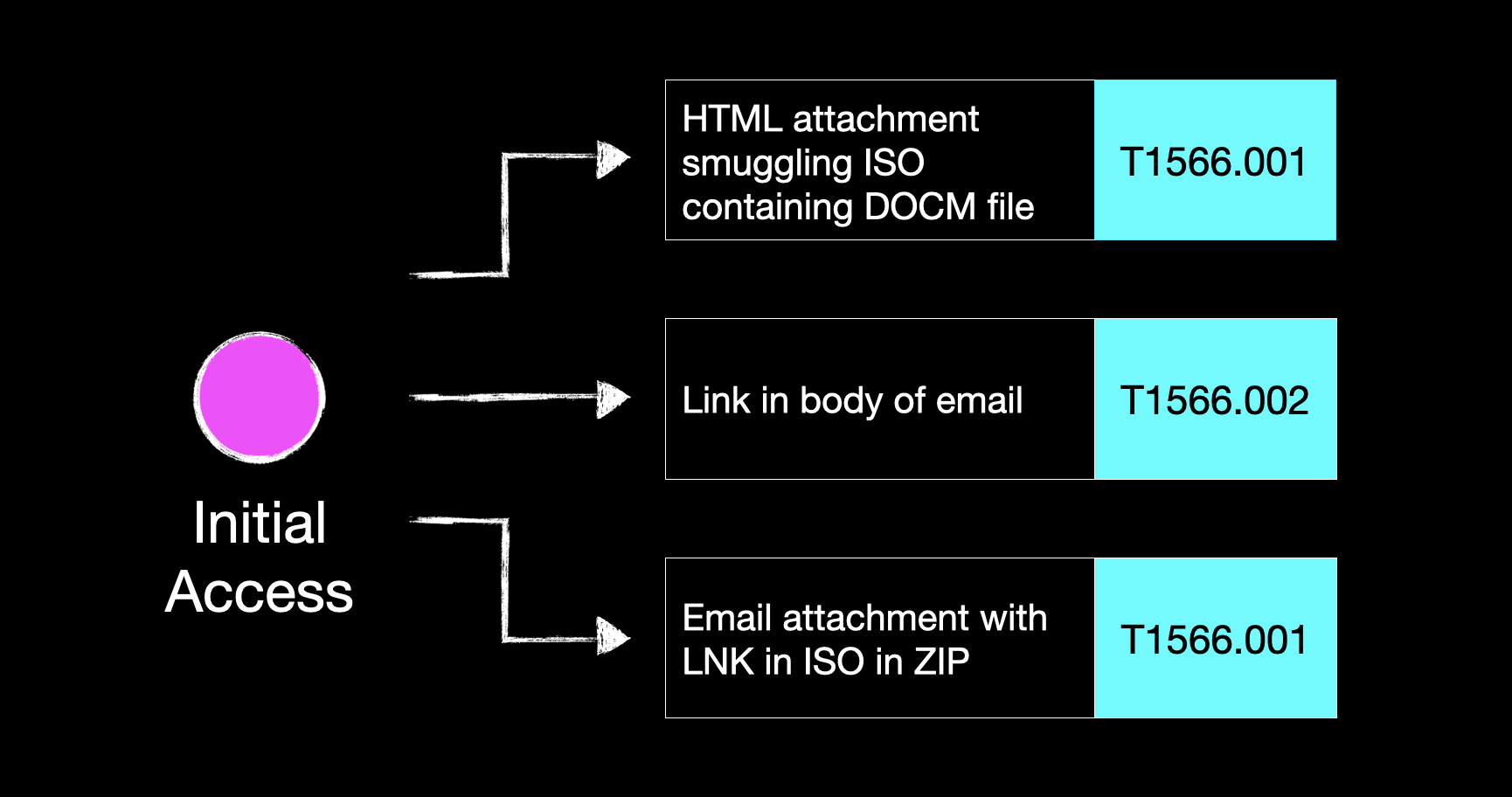

At the initial access phase, a link in the body of an email might’ve been our technique of choice here, maybe delivering a smuggled payload or hosting a credential-grabbing fake login portal. All cool stuff, no doubt, but what are we doing about all the other initial access vectors that a five minute scroll through Twitter might highlight?

How would our mail filtering fare against an HTML attachment that smuggles a macro-enabled Word document in an ISO, specifically designed to bypass Mark of the Web? What about an LNK shortcut file nested in an ISO within a Zip?

A couple of reasonably convoluted delivery methods, but both legitimately used by threat actors in the wild.

So let’s consider an alternative approach to our scenario-based purple team. An approach where, instead of an end-to-end chain, we took each tactic (initial access, execution, discovery, etc.) and generated a list of the techniques we deemed to be most important for testing.

What should we execute?

We’re in the phase of generating the body of tests we want to execute in our atomic purple team - how do we decided what should go into that and what should not? How do we prioritise? How do we even find attack technique permutations in the first place?

There are many sources to draw from here, but four of interest include:

- Threat Intelligence

- Incident Write-ups

- Offensive Testing Outputs

- Security Tooling Capability

The first two are probably the most obvious - we can take the published techniques of threat groups of concern to us and distill these into our test cases. Reading through content provided by The DFIR Report is a great resource for this, where we have high quality output listing individual attacker commands and overall objectives.

The latter two of these points are probably a bit more interesting. Firstly, offensive testing output. Here we’re considering the red teams, scenario-based purple teams, etc. that are performed in our environments (either by internal teams or vendors). If there are detection improvements highlighted in those reports, why not fold them into our atomic purple teaming? If our ability to digest threat intelligence and general offensive trends isn’t as mature, leveraging the insight of external offensive testers and the techniques they use could be invaluable.

Secondly, security tooling capability. This is a uniquely different perspective that atomic purple teaming offers up. In contrast to considering our organisation and our relevant threat actors first, we focus on what a given tool, or tools, should give us in terms of detective/preventative capability. Say our CISO has returned from BlackHat and we suddenly have a new blinky box that supposedly mitigates all manner of Active Directory identity attacks. We can take any vendor-produced material, as well as our own understanding of the problem space, and generate a test suite to put it through its paces.

There are three primary themes I would put forward for the test suites we create. The first is ‘threat actor focussed’. With an understanding of the threat actors we expect to target us, based on our industry vertical or other actor behaviours, we can leverage the threat intelligence and incident write-ups we previously mentioned to draw up a suite of test cases that considers these actor techniques in aggregate.

Alternatively, we could take a given technology (or technologies), and focus our test suite here. When I say technology, I’m not just considering our blinky box example above. Consider a new cloud platform being deployed by your organisation. You could evaluate this platform in its entirety, digesting any produced threat modelling output (or do your own!), and producing a test suite that provides confidence in the SOC’s ability to detect malicious activity taking place within it. Nick Jones and I wrote a whitepaper on this last year, which goes into this in more detail if you embark on this process!

Finally, there is the research theme. There is no shortage of great research put out by the infosec community that can serve as the impetus for your purple team exercises. Take harmj0y and tifkin_’s phenominal Active Directory Certificate Services research from last year. This offers a wealth of attack types to explore and could be the sole focus for a purple team exercise.

An example of test case generation

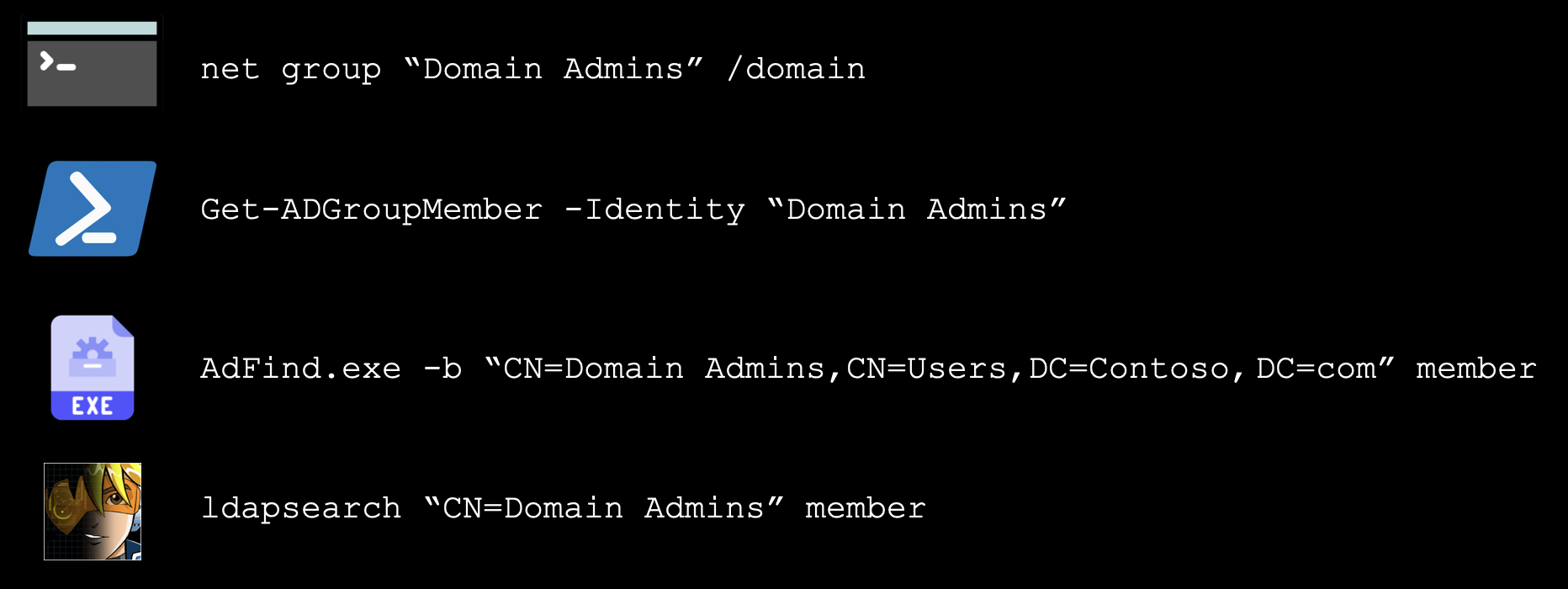

Let’s add some meat to the bones here and take a look at what this test case generation process could look like. We’ll use techniques that fall under MITRE ID T1087.002 as an example.

T1087.002 - Domain Account Discovery: The attacker will attempt to discover who is a member of the privileged “Domain Admins” Active Directory group.

Here we’ve got four examples of procedural actions we could perform for this technique (not the only ones possible, of course).

The initial net command is probably the most common means of executing this technique, and one we could leverage a Sigma rule to detect.

It might be that your EDR or other endpoint security tool alerts upon this out-of-the-box, or maybe not. How would it perform against a second test where we obfuscate the command?

Set GROUP=“Domain Admins”

n^e^t g^r^o^u^p %GROUP% /d^oDepending on the detection logic employed, this may still trigger, or maybe trigger a separate rule for the obfuscation technique used. The important outcome here is that we’re asking these questions of our defenses.

Consider the other three procedures in the slide above. Here we likely have to rely on different log sources. Our PowerShell command will require some Script Block Logging or similar, or some other telemetry provided by our EDR.

Usage of AdFind - every ransomware actor’s favourite third-party tool for AD recon! - might require different alerting logic, based on its command line arguments, or we might turn to our Anti-Virus or AppLocker logs for blocking/auditing information.

Finally, the in-memory execution of LDAP queries using a BOF or similar tool offers up another detection challenge. With no process creations or command-line arguments, do we have LDAP query telemetry from our EDR provider? Or some network or domain controller logs that could give us insight into these queries?

Obviously, there are many other permutations we could dig into here, including those simply targeting different high-value groups. The important takeaway is that many procedures can live under a single MITRE technique, and each might ask different questions of our detective toolset.

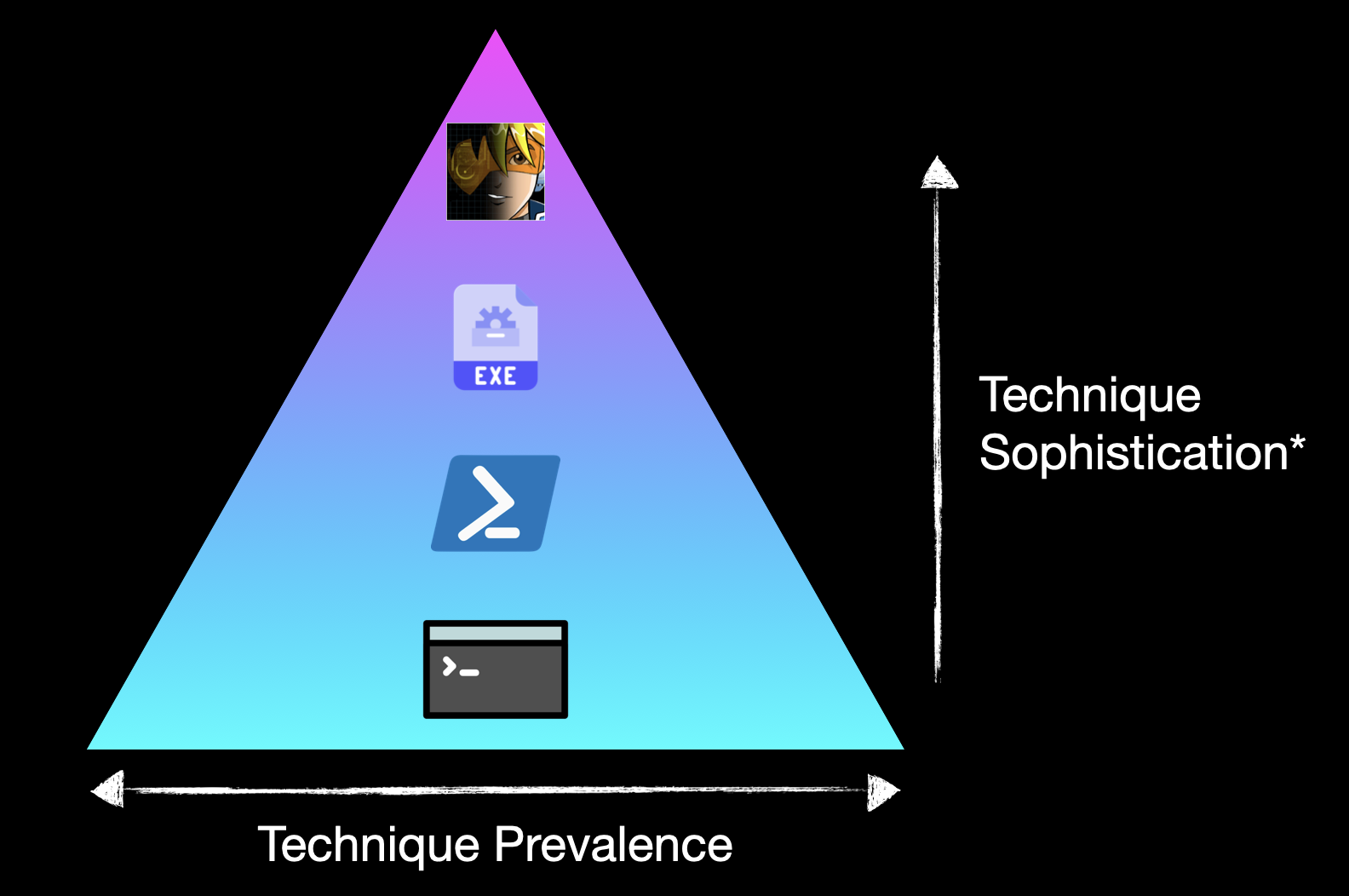

Let’s take our four example procedures and put them in some nominal sophistication pyramid, as above. You’ll note the asterisk on sophistication; the ordering isn’t really important here so if you feel that PowerShell should be above AdFind or something, that’s fine.

One final point to make here is that if you have a detection for the top of the pyramid - maybe due to anomalous LDAP queries coming from a given process - don’t take for granted that you have detections for all sophistication levels below it. As we’ve discussed, these all rely on different telemetry sources, and something relatively basic like our net commands might be a technique that our EDR has deemed too noisy to be a default alert. A bad assumption for us to make as we build up our detection capability!

Automation

Before we dive into the results we can capture from our atomic purple team, it’s worth mentioning the importance of automation. Automation amplifies many of the benefits of the atomic purple team methodology, not least of which repeatability and scalability.

If we define our techniques as code, they can be source-controlled and shared across teams that may not have the offensive skillset to run them manually. Considered as part of a detection engineering lifecycle, the repeatable nature of the automation means we can run techniques multiple times to confirm how they appear in logs and validate any use cases developed. This could then play a part in future regression testing too. Should we choose to, we could also run the same techniques with minimal effort across multiple environments.

There are several freely-available tools that facilitate this automation, and can bootstrap a purple teaming function without having to develop the code for a stack of techniques yourself. These include:

Results Data Produced by Atomic Purple Teaming

Once we’ve put together our test cases, we can start executing them and capturing results. There are three key data points I’d suggest you focus on recording (you might have others too, that’s fine).

Firstly, did it generate telemetry? It’s important to make a distinction here, in that we’re looking for actionable telemetry. In this context, that means two things in particular:

-

The logs are of suitably high-fidelity to identify the offensive action is taking place: Ultimately, you will have to be the judge of this, but an example might be a child process being spawned as part of Cobalt Strike’s

execute-assemblyfunctionality. Did we see arundll32.exeprocess spawning when it was executed? Yes. Is this enough to reliably and repeatedly detect this malicious behaviour? No. Therefore, this test case would be marked as a failure. -

These logs are available to the SOC for operationalisation: While we might have some high-fidelity logs from the point above, if the SOC cannot interrogate them, they’re of little use. An example of this might be a host running a well-configured Sysmon. While those logs will likely be invaluable for incident response, if they aren’t being shipped off to a centralised SIEM, they are of little value to the SOC. To summarise these two points, we’re looking for the right logs in the right place.

From an alerting perspective, things are much the same. Do we have high-fidelity alerts that accurately articulate the malicious action we’re testing, and are surfaced in a location the SOC are going to triage. If an alert is produced in a long-forgotten security portal that the SOC do not monitor, I’d suggest you could classify that as an alerting failure in the results.

The third result criteria is prevention. Fundamentally, we want to gain an understanding of what is possible in the environment from an offensive perspective. If we’ve invested effort in segregating our network, tuning our EDR to be as aggressive as possible, these results will provide technical evidence of that. This can also prove useful in prioritisation of remedial work; we might want to place a lower priority on developing alerting for techniques that are prevented, compared to those for which no mitigation (i.e. no alerting or prevention) exists.

VECTR is another freely-available tool that facilitates the capture of purple team results. It has a ton of features, but principally it allows you to track and produce metrics for purple team performance over time.

Applying Results - High-Level Evaluation

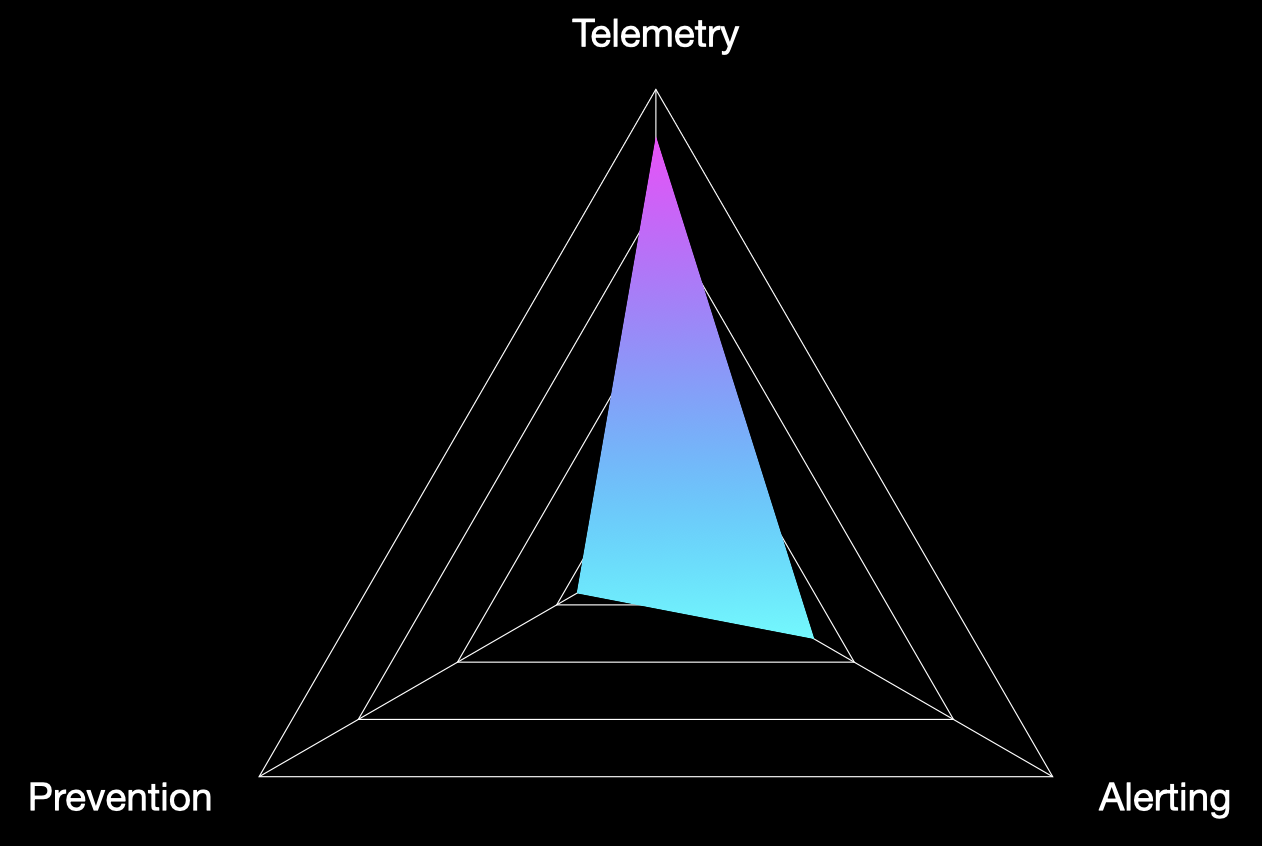

While you absolutely don’t have to execute test cases from across multiple MITRE tactics as part of a single atomic purple team, let’s assume we have, and we’ve captured the percentage of test cases for which we have telemetry, alerting and prevention. If we map those results on a graph, we might get something like the below:

Here we can immediately see strong telemetry coverage, with a poor performance in prevention, and a so-so performance for alerting. Now, the most effective means of understanding exactly why these results occurred is invariably to speak with the SOC or security teams to get a feel for their detection/prevention strategy, tooling and priorities.

Just glancing at the high-level results though, we might be dealing with a SOC at the start of its maturation journey. An initial investment in tooling might explain the high telemetry result, while the poor alert coverage could be the result of those logs (which we’ve deemed to be high-fidelity and in the correct location) not being leveraged to produce use cases just yet. Given we’ve run techniques from across MITRE ATT&CK in our example, the low prevention result might also give an indication of security hardening more broadly, with opportunities to tune mail filtering to prevent certain file types or an EDR configured more aggressively to prevent our Execution phase techniques.

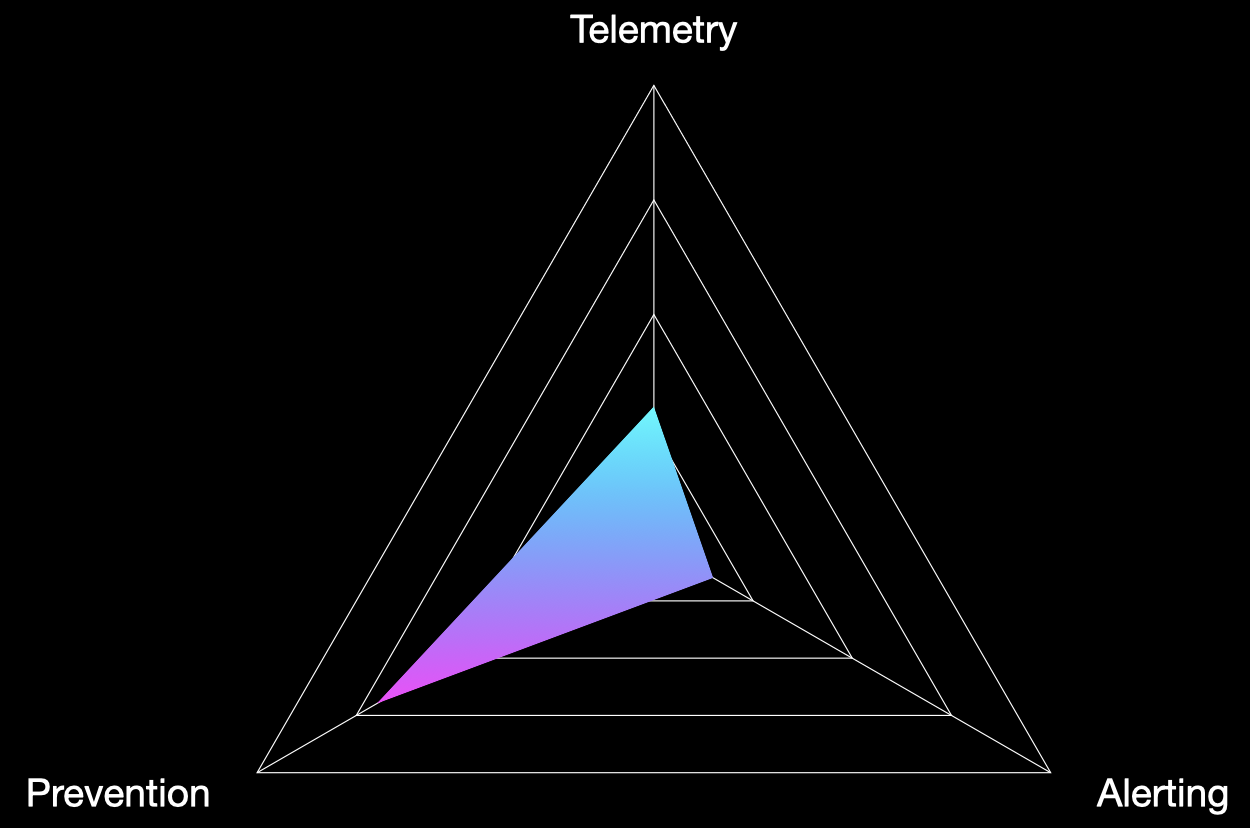

An alternative outcome might look like the above. Here we see a strong preventative outcome, but poor performance in other areas. While the prevention score is great, it might suggest that an actor that does achieve a foothold in the environment could take time to find bypasses for any hardening measures encountered, without the SOC being notified.

Applying Results - Business Outcomes

With an understanding of how and what we can do with atomic purple teaming, let’s consider some applications of the results. There are four key areas I want to call our here:

- Performance Benchmarking

- Environment Comparison

- Return on Investment

- Industry Comparison

Performance Benchmarking

Regular atomic purple teaming offers the opportunity to benchmark detection/prevention performance and track improvement or regression over time.

While the same could be said for other metric-generating testing, such as red teams, atomic purple teaming generates far more data that enables granular and direct comparisons with previous tests. This is assuming the test cases run from one exercise to the next are the same.

There are a couple of key challenges to highlight when applying atomic purple teaming in this way:

-

TTPs evolve over time: While we can get most accurate comparisons by repeating test cases from one purple team exercise to the next, the threat landscape changes over time. Techniques that were once hugely prevalent may die out, while others may gain popularity.

-

The choice of test cases is critical: Related to the above, the relevance of test cases to real-world threat is crucial to the overall success of the purple team exercise. If our test cases aren’t representative of what threat actors are doing, we might ace an atomic purple team and not achieve the main aim of helping our organisation improve its defences.

Environment Comparison

Performing atomic purple teaming across corporate environments also allows for comparisons to be made. This is particularly valuable in larger organisations, where the detection coverage may differ across, say, regional and headquarter offices. Similar comparisons could be achieved against different endpoint builds (e.g. a new EDR configuration, new operating system upgrade, etc.), or on-premise vs. virtualised builds.

The main challenge here is ensuring the techniques executed across environments are relevant to all test locations. If one of your environments is a Citrix server, you might want to understand the detection coverage for attempted breakouts, while this of course would not be relevant in other locations.

Taken to the extreme, could you compare the results of a purple team performed against a cloud native application in AWS to those of a Windows 11 build? Would that be a fair or useful comparison?

Return on Investment

We’ve already discussed how our atomic purple teams can have a security tooling focus, specifically designed to see what a blinky box is capable of. Thinking more broadly though, the output of a purple team can help demonstrate Return on Investment (ROI).

Consider our first results graph above, with the high telemetry. Assuming our organisation has the foundational capability to build new use cases, what does a high telemetry and low alerting combination tell us? Maybe we’re not getting the most out of the tools we’re already paying for, and we could squeeze more from the visibility they give us?

There are two absolutely crucial challenges to mention here. The first is around the conversion of raw telemetry into viable alerts.

Raw Telemetry != Viable Alerts

The percentage difference between telemetry and alerting is something you might call the alerting potential.

Once you start digging into this alerting potential, you’ll quickly realise that there’s often a chasm between having visibility of a technique being executed, and being able to discern whether that technique execution is malicious or benign.

A good example might be something like SysInternals’s PsExec. While usage is often relatively easy to identify, if it is used ubiquitously in your environment, it might be nigh on impossible to discern the malicious activity from legitimate administrative tasks.

The result of this then, is that you’ll always have some unrealised alert potential. A fact that can get lost when considering all your atomic purple teaming results in aggregate.

Alert Prioritisation

In my opinion, one of the most dangerous habits to get into with atomic purple team is adopting a ‘Whac-a-Mole’ mindset when it comes to remediation. Not all techniques are created equal, and the effort required to take an alert into production should definitely be spent in some areas over others.

Take the execution of a DCSync attack, compared with running whoami. While there’s the potential for a well-designed whoami use case to alert upon successful privilege escalation or web shell activity, in most environments, a well-tuned DCSync alert is going to be near the top of any SOC’s shopping list.

The key takeaway here is to ensure that context isn’t lost when results are aggregated and disseminated to your senior stakeholders. Those high-level stats can be immensely useful to articulate progress and development, but the test suites you devise are likely not a ‘completable’ thing, in the sense that there won’t be an achievable 1:1 relationship between technique and alert. There’s also the added complication of relevant TTPs changing over time, and senior leadership questioning how capability has inexplicable gone down from one purple team to the next!

Industry Comparison

The final application of results we’ll mention here is comparison across industry. This is particularly relevant when atomic purple teaming is conducted by an external party.

Every senior leader wants to know how well they’ve fared compared to other firms in their industry. Given the nuance in all the areas that we’ve discussed up to now, it’s clear that it’s not an exact science and a definitive score can’t really be applied. Nevertheless, they’ll still push to know!

This, as you might expect, has its own challenges. In the event that you’re giving security leadership some less-than-fantastic news, they’ll quite understandably want to know how they bridge the gap. How do they get a ‘better score’ next time?

Given the complexity involved in developing and maintaining a SOC (and indeed the other business functions responsible for bumping up that prevention percentage), you have to leverage your experience at this point, and be mindful of your areas of inexperience too.

Chances are, most people conducting these purple team exercises won’t have managed a SOC before, or even worked in one, so the best thing to draw on is what you’ve seen from other organisations. Consider our PsExec example. There might be a very good reason that the SOC doesn’t have a detection for it, and the right recommendation to make might be upstream in the form of ‘standardisation of admin tools and processes’ rather than telling the SOC how to detect PsExec for the 15th report in a row!

Weaknesses of Atomic Purple Teaming

We’ve already touched on many of atomic purple team’s weaknesses in this blog. The main issues are as follows:

-

It plays into a ‘MITRE ATT&CK Whac-a-Mole’ mindset: Dechaining our attacks into individual techniques is prime spreadsheet-fodder. Approached in the wrong way, it can push the wrong behaviours, particularly when it comes to remedial actions.

-

It doesn’t test response playbooks and processes: Running test cases in our atomic fashion doesn’t offer much opportunity for the SOC to test its ability to respond to attack. Having said that, it does surface alerts that many analysts won’t have seen before. It also gives them invaluable practice using their tools to interrogate telemetry.

-

Good ‘atomic’ performance isn’t the whole story: Given the above, it’s clear that an organisation that performs well in an atomic purple team isn’t certain to perform well in the face of a real attack. Assuming the test cases we’ve been using to uplift the SOC are well chosen, it’s reasonable to assume the SOC would have a greater likelihood of detecting an attack, but the response from that point onwards is outside of what our purple team can test.

-

There’s a level of maturity required to gain value and digest results: The dataset generated by an atomic purple team has numerous applications, not least of which as a backlog for detection engineering. But an organisation needs to have the relevant security functions and capabilities to digest these exercises and action their findings. As an example, if there’s no technical capability to generate custom use cases, or no team with the relevant skills to do so, the organisation might be unable to improve until some key building blocks are in place.

Conclusions

Atomic purple teaming offers a great means to inform strategy, prioritisation and investment. Combined with automation, testing can be performed scalably and repeatably, the latter being hugely beneficial to detection engineering and subsequent regression testing. Tools such as Prelude Operator, Atomic Red Team and VECTR can facilitate this.

Crucially, this method of purple teaming is only ever as effective as the validity of the test cases performed. While regular atomic purple teams offer usable metrics that can feed back into the business and give an indication of general detection capability, testing against the wrong offensive techniques ultimately encourages an organisation to develop its defenses against the wrong threats.